LA Times

From 2001-2007, the L.A. Times chronicled the progress of the Chouinard Foundation in numerous articles. These articles, written mainly by art writer Suzanne Muchnic, form an articulate summary of the Chouinard Foundation’s accomplishments. Numerous magazine articles were written by top art writers concerning the progress of the Chouinard Foundation as well.

LA Times Culture Monster

Chouinard, the influential L.A. art college

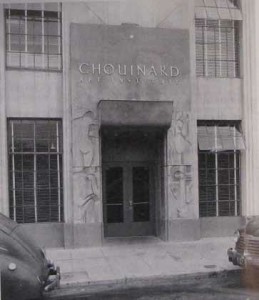

Chouinard Art Institute has come to life for the third time in 90 years — this time on the Web, where the high overhead costs that eventually sank the original, highly influential school in 1972 and blunted an attempted revival during the 20005 no longer will be a factor.

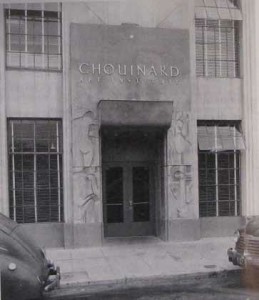

The Chouinard Foundation website is devoted to telling the story and documenting the influence of the art college (pictured) that a war widow named Nelbert Murphy Chouinard (pronounced shuh-nard) launched near downtown L.A. in 1921, continuing for more than 50 years until it was contentiously consumed in the creation of Cal Arts.

The Chouinard alumni roster includes Robert Irwin, Ed Ruch, Larry Bell, Allen Ruppersberg, Hollywood costume designer Edith IIead, graphic artist .John Van Hamersveld (designer of The Endless Summer” film poster and the Beatles’ “Magical Mystery Tour” and the Rolling Stones’ “Exile on Main Street’ album covers) and the “Nine Old Men,” the crew of animators who played vital roles in the triumph of Walt Disney.

The site offers videos, news articles and historical background on Chouinard’s initial run and the activities of the Chouinard Foundation, which began improbably in 1999 after Dave Tourje, an artist, guitarist and construction company owner, bought Nelbert Chouinard’s 1907 home in South Pasadena as a fixer-upper without knowing much about her, then became enthralled with the notion of restoring her legacy along with her former domicile.

Tourje and the late Robert Perine, an Orange County designer and Chouinard alum who created advertising graphics that helped push Fender guitars to world dominance, started the foundation and in 2003 opened a new Chouinard in a restored, 1901-vintage brick building in South Pasadena. Money problems forced it to close in 2006, but the foundation remained active, running art courses through 2009 in partnership with L.A.’s Department of Recreation and Parks.

Tourje says he began focusing on creating the website about 18 months ago. Its features include images from an archive of work by former Chouinard students, as well as places for Chouinard loyalists to share their recollections and photographs from student days.

One comment already posted is from Ruscha, who was at Chouinard during the late 1950s: “While another art school in the area had dress codes (ie: Art Center: no facial hair, no sandals, no bongo drums) Chouinard was free and easy. Shall I say more freedom for everyone? It was great and it worked.”

Chouinard kept working while Ruscha was there because an admiring Walt Disney pumped large sums into the operation, which in 1957 nearly went bankrupt because of an embezzlement. Starting in 1929, Nelbert Chouinard had given Disney animators scholarships on a pay-it-back-later basis to help them hone their skills. Disney died in 1966 and Chouinard in 1969. With the 1950s Disney gift, Tourje said, organizational control had passed to what eventually became California Institute of the Arts, a school pioneered by Disney. In 1972, when CalArts opened in Valencia, most of Chouinard’s faculty was let go.

In hindsight, Tourje said, it might have been smart to try to forge an official tie between the new web venture and the Gettys sweeping regional initiative, Pacific Standard Time: Art in L.A. 1945-1980. But he’ll settle for what he hopes will be a symbiotic buzz from all the attention now going to L.A.’s contemporary art history. “Pacific Standard Time is so pervasive, it almost doesn’t matter” that there’s no formal link, he said.

Other Chouinard Foundation activities include completing an hour-long documentary film about a teenager whose life took a turn for the better thanks to his studies in the late-2000s Chouinard-sponsored art classes at rec and parks centers, with the story widening to incorporate Chouinard’s institutional legacy. Another big dream, Tourje says, is raising an estimated $3 million to $5 million to buy back 743 Grand View St., the building near MacArthur Park that Nelbert Chouinard built to house her school starting in 1929. It’s now the home of New Times Presbyterian Church. Acquisition — which would require the help of major donors currently nowhere in sight — would make possible an attempt to restore “Street Meeting,” a proletarian political mural that David Alfaro Siqueiros created in 1932 on the wall of an inner courtyard while guest-teaching at Chouinard. It had long been painted and plastered over until being rediscovered in the mid-2000s.

Tourje says he’s also interested in getting the Chouinard Foundation back into the art-education game, via online courses offered through the website.

“The web allows us to be very economical and still be a very viable information platform,” he said.

RELATED:

- True to a significant school

- Chouinard packing its easels for good

- An art house revival: Mike Boehm

- Photos: Top, the Chouinard Art Institute near MacArthur Park during the 19305; school founder Nelbert Murphy Chouinard during the 1940s. Credits: Chouinard Foundation.

Letters Home

Los Angeles Times CALENDAR

Thursday, May 10, 2007 calendarlive.com

LETTERS

YOUR article on the Chouinard house in South Pasadena was very enjoyable [“An Art House Revival,” May 3]. Often, after a few sentences I will jump paragraphs looking for sub-stance. With your article, I settled into my chair and enjoyed the moment.

BOB O’CONNOR

Siqueiros 2010

Los Angeles Times CALENDAR

Sunday, September 12, 2010

FAMED MURAL: A colorized rendering of David Alfaro Siqueiros’ “America Tropical” (1932) on Olvera Street. A viewing area is under construction.

More than an activist

Murals, landscapes and a multimedia show reveal the many sides of Siqueiros.

SUZANNE MUCHNIC

David Alfaro Siqueiros is a giant of art and political activism in Mexico, where he was born in 1896 and spent most of his 78 years. His encounter with Los Angeles was brief — about seven months in 1932 — but it still reverberates in efforts to preserve “America Tropical:’ an incendiary mural on Olvera Street that was painted over soon after he finished it, and in the work of contemporary Chicano artists.

And now, in a serendipitous convergence of events, Siqueiros is having his biggest Southern California moment in decades:

- Construction of the mural’s shelter, viewing platform and interpretive center began last week at El Pueblo de Los Angeles Historical Monument and is expected to take about two years.

- Today, “Siqueiros: Landscape Painter:’ a major exhibition that reveals a little-known but powerful aspect of the artist’s work, will open at the Museum of Latin American Art in Long Beach.

- On Sept. 24, “Siqueiros in Los Angeles: Censorship Defied:’ a multimedia show about the artist’s Southern California sojourn and its aftermath, will begin at the Autry National Center in Griffith Park.

The independently organized exhibitions will tell part of a story that has waited too long to be told, says Luis C. Garza, a Los Angeles-based photojournalist, writer and documentary producer who met Siqueiros in 1971 at a world peace conference in Budapest, Hungary, and conceived the Autry show.

“Siqueiros changed the visual landscape of Los Angeles:” Garza says. “It took 30 or 40 years for the seed he planted to germinate. Now we are celebrating it in a manner that is giving the artist his due”.

Born in Chihuahua and raised in Mexico City, Siqueiros was the youngest of Mexico’s triumvirate of leading social realist muralists, including Diego Rivera and Jose Clemente Orozco. They were all trained at the San Carlos Academy of the National School of Fine Arts, but developed individual styles partly shaped by political and social unrest in Mexico. He joined a revolutionary movement while still in his teens, beginning a long engagement with Communist and militant activities that often put him in conflict with authorities and occasionally landed him in jail.

With the help of friends, Siqueiros escaped house arrest in Taxco to come to Los Angeles, where he produced three murals, his only such works in the U.S. “América Tropical” is on a second story exterior wall of Italian Hall and eventually will be seen from an extension to an adjacent building. The mural’s central image — and source of controversy — is a Mexican Indian tied to a cross, crowned by an American eagle.

Another L.A. mural, “Street Meeting,” featuring a labor organizer addressing a crowd, has long been buried under paint and structural components of a Korean church that formerly housed Chouinard School of Art. Discussions about uncovering the mural began five years ago but no resolution has emerged. “Portrait of Mexico Today,” a commentary on Mexican political and social conditions commissioned for the home of filmmaker Dudley Murphy, was moved to the Santa Barbara Museum of Art in 2001.

Siqueiros’ exile in Los Angeles ended in November 1932 when he was denied a visa extension. He traveled on to Argentina and Spain, where he fought in the Spanish Civil War, and returned to Mexico in 1939, but not to a peaceful existence.

No exhibition can encompass all the turmoil and passion of Siqueiros’ life and art. But the Autry and MOLAA shows offer fresh perspectives on the artistic achievements and social convictions of an artist whose local presence will grow when “América Tropical” goes on view. An effort to uncover the mural began in 1969 but didn’t gather force until 1988, when the Getty Conservation Institute teamed with the city department that administers the site. The Getty Foundation has spent $3.95 million on the project and the city has contributed $5 million, but completion has been repeatedly delayed by bureaucratic entanglements, personnel changes and technical problems. The construction project announced Wednesday is expected to take about two years.

Jonathan Spaulding, executive director of the Autry’s Museum of the American West, says that “Siqueiros in Los Angeles: Censorship Defied” will introduce a story line to be continued at the downtown Los Angeles mural center. Unlike the landscape exhibition in Long Beach, the Autry show is, in Spaulding’s words, “a narrative about Los Angeles that uses Siqueiros and a generation of artists who came after him as a lens to look at the identity of the city and trace the recognition of its Latino identity, very contested in the 1930s and now celebrated. Siqueiros launched a movement not only of street art and murals in public space, but also a movement to reconceptualize the identity of Los Angeles.”

The assembly of about 100 paintings, drawings, photographs, reproductions and historical documents begins by outlining the artist’s formative years, then sets up a broad artistic and social context for his Los Angeles visit and delves into the production and official rejection of “América Tropical.” The show also explores Siqueiros’ materials and techniques and how the badly faded mural has been carefully conserved but not repainted by the Getty Conservation Institute.

In the final section, works by Los Angeles artists including Barbara Carrasco, Judy Baca and Wayne Healy indicate how Siqueiros’ legacy has continued. A video presentation of murals in Southern California is accompanied by interviews with the artists who painted them.

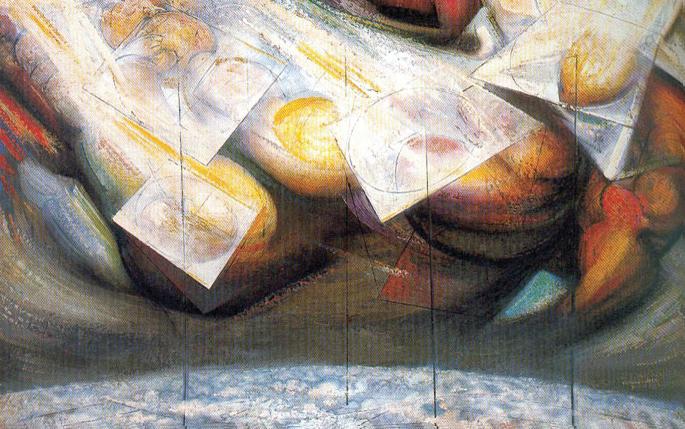

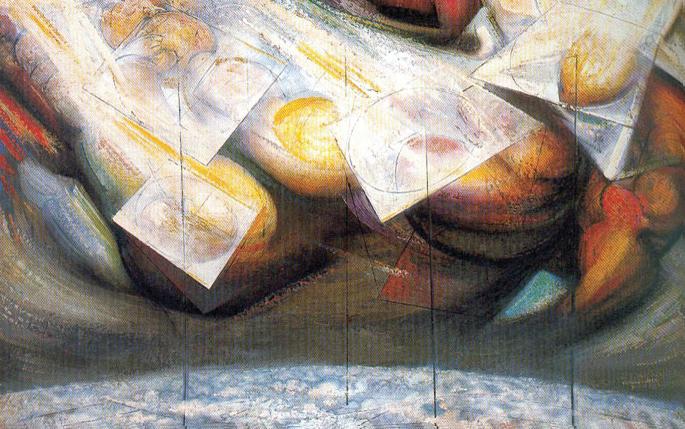

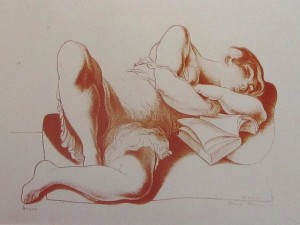

ARTIST WITH A COSMIC VISION: Stratospheric Antennas

shows lines projecting from volcanos to floating forms in the sky.

For museum visitors who know Siqueiros only as a hard-hitting muralist, the landscape show in Long Beach may come as a shock. But he painted landscapes throughout his career, including periods of incarceration, and they are obviously from the hand of an artist with enormous energy, deep feelings and strong convictions.

Organized by the Museo de Arte Carrillo Gil in Mexico City and curated by Itala Schmelz and Alberto Torres, the show of about 75 works — roughly half the landscapes Siqueiros painted — is teeming with emotion and drama. Trees all but explode, oceans roil and mountains rise to awesome heights. Nature can be threatening or magically wondrous, but it never sits still.

Cynthia MacMullin, MOLAA’s senior curator, who coordinated the Long Beach exhibition, describes Siqueiros as an artist with a cosmic vision. In a painting called “Atomic Aircraft,” he dreamed up a sort of organic spaceship and set it adrift on a curved wood panel. In “Stratospheric Antennas,” also painted on a curved surface, thin lines projecting from volcano peaks extend into a sky full of floating forms, possibly UFOs.

The subject matter of other works is easier to identify, but it may be presented from an aerial view or a low vantage point. In “Rocks With Figures,” viewers look up at women walking along the ridge of a volcanic rock cliff. It’s one of many works portraying people at one with nature. But others portray armies of miniature figures dwarfed by huge trees or mountains.

Still other paintings grapple with the effects of human force. “The Explosion of Hiroshima” protests the bombing of Japan that ended World War II. Abstract paintings of futuristic cities seem to praise modern ingenuity while warning against urban sprawl.

“The paintings are very sensual,” MacMullin says. “They make you feel as if you are part of the scene.” And most are packed with energy. “It’s all about cinematic movement,” she says. “Everything is in action.” But whether the action is creative or destructive — or both — is open to question.

Siqueiros did not paint from nature, as Schmelz and Torres point out in an introductory statement. “He was not a lover of nature in a botanical sense; on the contrary, his approach was that of a modern man who establishes a relationship between force and mastery.”

MAN OF MANY SIDES:

David Alfaro Siqueiros

Los Angeles Times

HOME

A MEETING PLACE AGAIN: David Tourjé and wife Linda gather around the dining room table of his design with their son Kyle,

right, and friends in the 1907 home, a former art salon.

An art house revival

A would-be teardown in South Pasadena is inspiration for a modern-day salon framed by its eccentric past.

WHEN Dave Tourjé bought the de- cripit 1907 farmhouse nearly 10 years ago, he didn’t have a clue it would become South Pasadena Cultural Land- mark No. 44. Rescuing the structure from certain teardown status was more about math. “It was twice the amount of money I wanted to pay and five times the amount of work I wanted to do,” he says. “But in that neighborhood, houses that were half the size were way more expensive.”

At the time, the 47-year- old construction firm owner – who for the last two decades has spent the better part of his work week as an artist, reverse- painting rebuses on acrylic panels – found it only mildly interesting that the house had belonged to Nelibertina “Nel- bert” Chouinard, founder of one of the earliest and most prestigious professional art schools in Southern California. Only when he mentioned the name to his father did he learn that his aunt had been a Choui- nard student.

After talking with that aunt, Tourjé felt the Chouinard lega- cy begin to resonate within his walls. The story it told – of the charismatic Minnesota-born painter who started her own Los Angeles art school in 1921 – suggested how the Monterey Colonial farmhouse might live on for a new generation. In its heyday, the home had served as a salon for local artists, a place where Chouinard faculty, stu- dents, graduates and their artist friends could exchange ideas and admire one another’s work. Tourjé’s goal was to restore that spirit, to re-create the essence of Chouinard’s salon but in his own way.

“The primary reason the house was nominated as a landmark in 2000 is cultural, not architectural” says Glenn Duncan, president of the South Pasadena Preservation Foun- dation. The property was sig- nificant because it played a crit- ical role in “fostering a collegial atmosphere for local artists and for students.”

LIKE a scholar, Tourjé re- searched the school, which operated near MacAr- thur Park in L.A. before it closed in 1972, three years after Chouinard’s death. He reached out to former teachers and stu- dents such as painter Ed Rus- cha, minimalist sculptor Larry Bell and Ojai potter Otto Hei- no. By 1999, a year after moving in and completing the first round of renovations, Tourjé had become a guardian of Ch- ouinard’s history, the house his chief artifact.

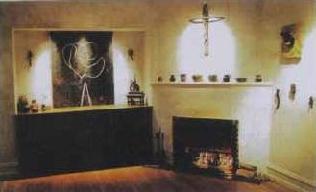

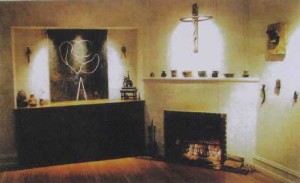

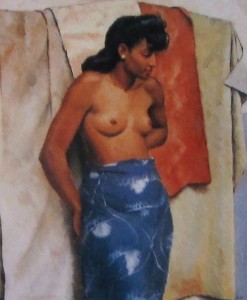

DISPLAY: A painting by the late Chouinard instructor Emerson Woelffer hangs over a Tourjé cabinet.Tourjé’s ceramics sit on the mantel

“I was surprised to learn that something so important had existed in a city that I con- ceived of having no history,” he says. “I wanted to make sure it was remembered.”

Tourjé joined forces with Robert Perine, a former student and historian of the school, to create the nonprofit Chouinard Foundation and revive interest in the institution and its illus- trious graduates, who include costume and fashion designers Edith Head and Bob Mackie, Echo Park ceramist Peter Shire, surf and rock graphic artist John Van Hamersveld, Warner Bros. cartoonist Chuck Jones and a host of Disney’s original crew of animators.

Many of these former stu- dents donated work to the foundation, which, after resur- recting the school from 2002 to 2006 in South Pasadena, now runs classes in conjunction with L.A.’s recreation depart- ment at the Exposition Park Intergenerational Community Center. The foundation also runs a program allied with the arts group KAOS Network in Leimert Park.

WIDE OPEN SPACES: The Tourjé’s home, originally built on 20 acres of citrus groves, evokes the spirit of a Southern country house with its second-story terrace and large front yard

These recent efforts have stayed true to Chouinard’s vi- sion, says Charles Swenson, a 1963 graduate of the school’s animation program and former creative producer on the TV cartoon “Rugrats.”

“She believed that art was for everybody and education should be affordable,” Swenson says. “She believed that art would make you a better per- son. If you studied you might not become the greatest painter in the world, but you’d be a bet- ter gas station attendant be- cause of it.” Tourjé, Swenson adds, “brought Chouinard house back to blossom as a sa- lon.

“It is not cold and austere like a historical house, but someone’s home where art and artist’s gather. It’s such an invit- ing place. The French doors of the living room open out into the front yard and the world, beckoning people to come in.”

That, however, was not how Tourjé found it. The Glassell Park native was living in Eagle Rock when he first drove by the South Pasadena house.

BELTS OF STEEL: A steel conveyor belt chair made by Tourjé.

PERSONAL GALLERY: Dave and Linda Tourjé in the living room, which, like the rest of the house, is filled with Chouinard artists’ work and pieces by the Tourjé s and friends.

“It was a completely impen- etrable thicket overgrown with trees and shrubs and vines,” Tourjé says. “I actually said, ‘God help whoever buys this thing.’”

He passed the house again a few months later as the owner, a real estate broker, was leaving.

Tourjé got a better look, notic- ing a tree that was one of the biggest flowering pears he had ever seen – “so old, it must’ve been planted with the house.” He noticed a small concrete pond and fountain studded with Batchelder tiles. Inside the house, he found Douglas fir flooring, old doorknobs, cop- per hardware and other period details.“At that point,” he says, “the house really started to commu- nicate to me.”

It spoke in an architectural polyglot. The home, originally on 20 acres of citrus groves, is defined by a colonnaded side porch facing the street. A ter- race runs the length of the sec- ond story, giving the house the profile of a Southern country house. The Batchelder tiled fountain on the back patio has the decoration of the Arts and Crafts movement popular in turn-of-the-century Pasadena. A 1919 addition to the house is Spanish-influenced, with a winding staircase leading from a second-story sleeping porch to the garden below.

“The house is an eclectic mix of early 20th century styles, an organic work in progress that evolved as Nelbert Choui- nard needed it to,” preserva- tionist Duncan says. “And it is stamped with her own creativ- ity.”

In much the same way, Tourjé had to approach the res- toration of the house with all the imagination he could mus- ter. The previous owner had passed on dozens of low-ball bids on the house when Tourjé proposed leasing and fixing up the house for 18 months, with rent going towards his future purchase of the prop- erty. As the proprietor of a firm that specializes in foundation and hillside repair, however, Tourjé could do much of his own contracting work, which kept initial upgrades to around $100,000.

One thing he didn’t attempt was a structural overhaul. The 2800-square-foot house has five bedrooms and 2 ½ baths, plen- ty of space for his kids Camelia now 21; Kyle, now 17; and Ala- na, now 15. “We just settled in and dealt with the house on its own terms,” Tourjé says, add- ing that Chouinard’s additions were made with humble ma- terials and without regard for architectural conventions. “The house really has a sense of her blithe spirit. It’s like an old shoe, worn in and comfortable.”

The kitchen, which had been modernized by the pre- vious owner, needed to be gutted. Tourjé, who has made stainless-steel and concrete fur- niture since the 1980s, poured concrete countertops and used structural rebar to support a cantilevered breakfast bar, un- der which sit 1950s-style metal and rattan stools from Pier 1.

He also made a dining table topped with concrete that’s im- printed with eucalyptus from the backyard.

“Everything I took out of the house or found on the property I tried to use again,” Tourjé says. He stripped doors,replated hardware and disas- sembled the arched glass facade of a china hutch and installed it as a kitchen window over- looking the backyard. Original pantry cabinets that had long been consigned to the garage were dusted off, sanded down and repurposed. The uppers now sit as a console in the front entry hall; the lower cabinets, complete with a mahogany top, found new life as a vanity in the master bathroom.

ALL OF this work was done with few photo- graphs or resources to provide directions. “The good news was that the house hadn’t been touched,” Tourjé says, laughing.

“That was also the bad news.” To get the original color for the exterior, he had to scrape off 10 coats of paint on the sid- ing and computer-match the right shade of vintage taupe. Inside, on the assumption that the house might host art shows, Tourjé installed dozens of re- cessed lights in the freshly fin- ished ceilings. “I destroyed the entire paint job.”

It was a wise move, though, as the house soon filled with Chouinard artists’ work dis- played alongside pieces by Tourjé, his family and friends.

The smoking room, and enclosed space that was likely a porch where men enjoyed their pipes, has a bench de- signed by Tourjé and sculptor Brad Howe. Elsewhere, walls are covered with framed works, including head studies drawn by Disney animator Don Gra- ham and the iconic poster for the 1966 surf film “The Endless Summer,” designed by Choui- nard graduate Van Hamers- veld. A collection of World War II-era snapshots with hand- written captions by Tourjé’s father hand in a cluster on the upstairs landing. In the master bedroom, Otto Heino pottery sits on a Scandinavian-style dresser.

The living room’s 1985 painting by the late Chouinard instructor Emerson Woelffer hangs over a black walnut cabi- net built by Tourjé, topped with low-fire pottery from Nicara- gua and a 1930s-era Dada ma- chine sculpture. Tourjé’s high school ceramics sit on the man- tel, and the wall above it is cov- ered by totems he made from sticks, rocks, cans and wire.

“It’s about creating some kind of aesthetic harmony with things that are just laying around,” he says. “I pick up a scrap of something, find ma- terials that communicate with it and construct a piece that works.”

Tourjé has done just that with the house, building a home that not only preserves the memory of the school and its founder, but also creates a livable space for his family. That is perhaps the greatest dif- ference between now and then: the presence of children.

“My Aunt Nelbert wasn’t a kid person, and it wasn’t really a kid house,” says Chouinard’s great-niece, Karen Lawrence, a New York-based commercial artist. “She was pretty formi- dable, truly a diva. She used to charm all these important art- ists into teaching at the school, and she did it all with blarney because she couldn’t offer them a thing.”

South Pasadena historian Duncan says Tourjé’s restora- tion has given a future to a relic of the past.

“Nelbert Chouinard was a widow. Her children were the students of the school,” he says. “Dave’s kids are living, breath- ing contemporary teenagers who made a house that was on its last legs come alive again.”

ART SCHOOL AESTHETIC: Pieces done by Tourjé decorate a living room wall, left. A lamp, center, made from a beer keg

lights the second-story porch. Decorated guitars, right, dress up a bare corner atop restored Douglas fir flooring.

The house has been ap- proved as a Mills Act property, a designation that provides tax breaks for restored landmarks. Tourjé says the family is mind- ful of their obligations living in a house devoted to art and filled with history, but they haven’t struggled with it.

“There was really no way with three kids, three dogs, two cats and a bird that we could live in a house that constrained our lifestyle,” he says. “We were able to fall into it naturally and be ourselves.”

On a recent Sunday after- noon, as the teens rummaged through the refrigerator be- fore dinner, daughter Camelia recalls those days back in ’98, when she was 12 and the family had just moved in.

“I wasn’t sure I wanted to live there,” she says. “But art is a common interest for everyone in this family, and it brought us closer together.”

She moved out this year to live closer to the school at which she teaches, but she fre- quently finds herself returning to her family home and all that it represents. “Although it’s an artistic house and landmark, we were always able to use it, to have gigantic birthday parties on the front lawn and friends stay over. It was a great place to grow up, and even more of a home because of all its memo- ries and history.”

Los Angeles Times CALENDAR

LEETERS

Mayor steps up in support of the arts

THERE will always be naysayers, but the fact that we have a mayor with a stated purpose of support toward the arts is something that should be focused upon. The Chouinard School of Art was awarded the first public-private initiative, which the mayor approved, to bring our art education program to the children and teens of L.A. through the Department of Recreation and Parks. In this, the city provides all space, materials and assistance in the arts, not empty statements.

DAVE TOURJE

Los Angeles

Tourje is the executive director of the Chouinard School of Art.

Los Angeles Times CALENDAR

Chouinard to boost education in the arts

The foundation will hold classes and bring in artists to underserved public recreation centers.

By SUZANNE MUCHNIC

Times Staff Writer

Three months after closing its art school in South Pasadena, citing insufficient funds and student interest, the Chouinard Foundation has formed a partnership with the City of Los Angeles Department of Recreation and Parks to provide art education for the city’s youth. Under the terms of an agreement approved by department commissioners Thursday and expected to be endorsed by Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa, the foundation will conduct classes and bring visiting artists to public recreation centers that have offered little or no art instruction.

No new city funds will be allocated to the program, said Kevin Regan, assistant general manager of the department.

The city will provide space in existing facilities, support staff and art materials, he said. The department and the foundation will work together to obtain private funding for classes and special projects.“This will be free-form art education with drawing and painting as the base,” said David Tourje, executive director of the foundation. The highlight, he said, will be visits from accomplished artists who will share their expertise and in- sight into processes of creative expression.Regan said he conceived of the partnership after reading about the closure of the Chouinard School of Art, a modest reincarnation of a L.A. college that closed in 1972. Partially funded by Walt Disney, the original school eventually morphed into CalArts in Valencia.

Last month, the foundation ran a pilot program — organized by artist Doris Kouyias, with the help of other artists including Gilbert Lujan and Wei Lo at the Exposition Park Intergenerational Com- munity Center. The first phase of the new program is expected to begin in late fall at the center, a multipurpose facility in a former swimming stadium. Belinda Jackson, executive director of the center, is facilitating grant applications.

Regan said that plans call for expanding the model into the department’s Clean and SafeSpaces, or CLASS, program, designed to help teenagers at risk in 47 centers throughout the city.“We have dedicated teen clubs in these centers,” he said. “Why not have Chouinard come in, teach the kids art techniques, maybe have them decorate their own clubs and go from there? If we save one kid from getting involved in gangs or turning their life to drugs, and if somebody who gets turned on in this program makes a good, life-changing decision, we have done a good thing.”

Chouinard packing its easels for good

The school, a spiritual heir to the famed L.A. art college, struggled from its 2003 start to attract students and funds

After struggling three years to keep alive a modest reincar- nation of Chouinard, a famous long-vanished L.A. art college, the artists and art patrons who established its spiritual heir in South Pasadena have decided there isn’t enough money or student interest to continue.

Barring a miracle, the Ch- ouinard School of Art will close when spring classes end Sun- day, Executive Director Dave Tourjé said.

Since 2003, the school has offered year-round instruction in a renovated, 101-year-old brick building at 1040 Mission St. but has had no accredita- tion or degree program. The staff consists of 10 part-time teachers and four office work- ers, only one of them full time.

Chouinard typically has 145 students enrolled, Tourjé said – about 100 fewer than it needed to break even.

Tourjé, an artist and con- tractor, said he and three other volunteer board members were so caught up in the day- to-day demands of running the nonprofit institution that they didn’t have time to build a broader donor base to back their vision of an art school run by artists. The school failed to generate the $360,000 a year in tuition and donations needed to meet expenses, he said, and the directors wound up floating annual deficits of $180,000 out of their own pockets.

The decision to stop came after a fundraiser raffle and art auction, scheduled for Satur- day, had to be canceled because of tepid response. A panel dis- cussion the same evening also will not take place.

“It was a pretty impossible task,” Tourjé said. “We knew what we were getting into. This kind of project can only sur- vive with massive support. We have very illustrious artists on our advisory board, but we ask them for advice, not money.”

The effort to reestablish Ch- ouinard began in 1999, when Tourjé teamed with artist Rob- ert Perine to create a founda- tion to fund and operate the school. Perine was a Chouinard Alumnus who felt dispossessed after the original debt-ridden institution closed in 1972, sub- sumed by Walt Disney in a fi- nancial bailout that eventually resulted in the creation of the California Institute of the Arts in Valencia.

DIRECTOR: Dave Tourjé has plans for the parent foundation.

In 1985, Perine published a history of Chouinard and its demise, titled “Chouinard:

An Art Vision Betrayed.” His death at age 81 in 2004 was “a difficult blow…He was a prime mover in the whole project,” said Tourjé, who is not an alumnus of the old Chouinard but became fascinated with its history when he bought a fixer-upper in South Pasadena that had been the home of Nel- bert Chouinard, who founded the college in 1921.

Although the school will die, Tourjé said that he and the other board members planned to keep its parent Chouinard Foundation alive. They’ll take some time for planning, he said, then try to become active in grant-making, although with the school’s closing the founda- tion’s resources “will be pretty much down to zero.” A prom- ised bequest gives the founda- tion hope for the future, Tourjé said, and the hope “to find gift- ed artists and invest in them in a very focused way.”

The foundation poured $450,000 into renovating and seismically stabilizing a former grocery that was “vacant and unusable” and turning it into a school, Tourjé said. Taking donated materials and sweat equity into account, he said, the value of the makeover topped $1 million. In return, he said, the building’s owner set the rent at about half the market rate.

“We helped the progression of development on Mission Street and created a building that could be construed as a centerpiece of the West Mission Street district,” Tourjé said. At the same time, he said, “I don’t think our departure will sig- nificantly impact development there. The city has plans for de- velopment that we didn’t affect. We were an unexpected arrival, an out-of-the-blue bonus. But we did bring more profile and appeal to the area.”

Glen Duncan, who chairs South Pasadena’s Cultural Her- itage Commission, expressed sorrow at the school’s impending demise, saying he had helped bring it to the area and saw it as an asset for the city.

He agreed, however, that its loss would be unlikely to ham- per prospects for development. The school did such a terrific job of restoring the building, he said, that it should not be difficult to find a new tenant. “They’ve helped raise the devel- opment bar in the city,” he said.

Tourjé said the school’s fail- ure to thrive can’t be attributed to a single factor. “I think you can get into the larger question of apathy toward the arts.”

The instructional focus was what the executive direc- tor called “the core of the old Chouinard’s success, meaning drawing, painting and design.”

This “pure-art” philosophy may have struck some poten- tial students as old-fashioned, he acknowledged. The prevailing notion in art education, Tourjé said, is that “you go to art school, you get a degree and then you are an artist. We disagree with that completely. We don’t have any ideas about degrees making a person an artist.”

Tourjé said the foundation will relocate to its previous headquarters, in Eagle Rock.

“We don’t view this as Ch- ouinard’s end. We view it as a transition and a new beginning of some kind.”

Los Angeles Times CALENDAR

They’ve barely scratched the surface

Under layers of paint and structural work, a 1932 mural by David Alfaro Siqueiros is found. Will it ever see the light of day?

By SUZANNE MUCHNIC

Times Staff Writer

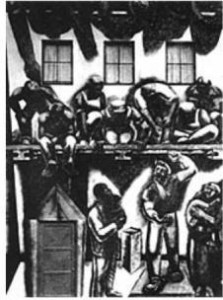

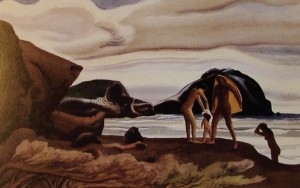

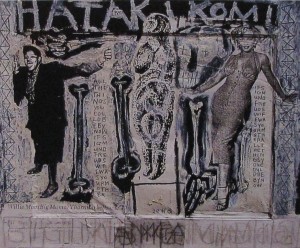

Astocky fellow with an open shirt baring his powerful chest stands on a makeshift podium, raising a fist and extending a hand as he appeals to his ragtag audience. A black man, transfixed by the soapbox orator, stands to one side cradling a child in his arms. A downtrodden white woman, also holding a child, watches from the other side. Above the speaker, dark- skinned laborers crouch on scaffolding and hang over the edge of a roof as they devour every last word of the message.

This is “Street Meeting,” a24-by-19-foot mural painted in 1932 by Mexican artist David Alfaro Siqueiros at a now- defunct art school near Ma- cArthur Park. It’s one of Los Angeles’ most important public artworks, and it vanished soon after it was created.

Some artists who assisted Siqueiros have told historians that faulty materials were to blame. Others have said that the painting was obliterated be- cause of objections to the subject matter. As time passed and memories dimmed, the school established as Chouinard School of Art and later known as Chouinard Art Institute – evolved into CalArts in Valencia. In typical L.A. style, the old building became the home of one Korean church, followed by another, and the mural was

all but forgotten.

‘A GREAT FIND’: One of Los Angeles’ most important public artworks, Siqueiros’ “Street Meeting” vanished soon after it was created. Most of the mural is seen here in a photograph taken decades ago.

Until now, a small group of Siqueiros and Chouinard enthusiasts, bolstered by a team of professional paintings conservators, had discovered that the two-story work is at least partly intact. Its condition is unknown, and large areas may have been lost or damaged. But preliminary tests indicate that “Street Meeting” did not flake off or wash away, as often reported. It is buried un- der several layers of paint, on a wall that has been divided by a roof, partly tiled and roughly patched. Indented lines in the upper wall conform to contours of images in the mural. Nail holes and small excavations reveals vivid color.

“This is mind-blowing,” said Dave Tourjé, an artist, contractor and executive director of Chouinard School of Art in South Pasadena, a 2-year-old recreation of the original institution. He discovered the location of the mural last summer but didn’t go public with the news until he had discussed the situation with current own- ers of the building and engaged conservators who could verify the existence of the painting and assess its condition. The conservators completed their first round of tests Wednesday.

The project faces enormous challenges. But if “Street Meet- ing” can be saved and put back on public view, Tourjé said, it will restore “something very culturally significant” to the community.

The turning point for the artist Siqueiros painted three murals in Los Angeles during asix-month sojourn. His only outdoor paintings in the United States, they mark a turning point in his development, said Los Angeles-based art historian Shifra M. Goldman, a Latin America specialist who has written extensively about his work.

The masterpiece of the trio, “América Tropical,” stretches across the second floor of a his- toric building on Olvera Street. Painted over within a few years of its unveiling because of its political content – though not before it had faded badly – the18-by-80-foot mural is the subject of a massive conservation effort that has dragged on for nearly two decades. Another Siqueiros mural, “Portrait of Mexico Today,” an 8-by-32-footpainting commissioned for the patio of a home in Pacific Palisades, was restored to nearly pristine condition and moved to the Santa Barbara Museum of Art in 2002.

The Chouinard mural, the first of the L.A. works, is a seminal piece, Goldman said,

representing his search for an expressive style attunes to revolutionary ideals and illuminating his experiments with airbrush painting on cement.

Conservator Leslie Rainer, a veteran of the Olvera Street mural project who heads the team studying the Chouinard paint- ing, called it “a great find” for the city and the art community. “If we are able to recover it,” she said, “it will give scholars and conservators an opportunity to learn much more about Siqueiros and his mural painting technique in Los Angeles. It will also give the city one more potentially great ex- ample of his mural work.”

Siqueiros, who died in 1975, was an influential figure whose work throbs with revolutionary fervor and aesthetic muscle. Allied with Diego Rivera and José Clemente Orozco and best known for fiery murals in Mexico City, he promotedlarge-scale wall painting as a public forum for social justice. He found his political voice as an art student, helped unionize fellow artists and concentrated on Communist Party affairs from 1925 to 1930, when he was imprisoned for his political activities and confined to Tax- co, in southern Mexico.

Siqueiros traveled to Los Angeles in 1932 – perhaps at the invitation of Nelbert Murphy Chouinard, founder of the art school – and report- edly got help across the border from film director Josef von Sternberg. While in Southern California, he painted portraits and murals, gave lectures and spent a few weeks at Chouinard, teaching a class in mural painting and producing “Street Meeting.” It was unveiled July 7, 1932, to a crowd of 800.

Uncovering and preserving the mural is a long shot. The conservators must do addition- al tests to determine how much of the painting might be saved, formulate a plan and establish a budget. If the project appears to be feasible, money must be raised, and not just for art conservation. A protective structure would have to be erected over the exposed top half of the mural. A roof, probably added in the 1940s, enclosing the bot- tom half of the painting in a room now used as a kitchen, would have to be removed or cut back. To accomplish all that, the building probably would have to change hands.

But Tourjé and Moses Cho, pastor of New Times Presbyterian Church, which has owned the old Chouinard building for the past 10 years, say the mural may be the key to both men’s dreams.

Tourjé – who became in- tensely interested in Chouinard after purchasing a fixer-upperhouse in South Pasadena that turned out to be the former home of the school’s founder – approached Cho in 2001 about buying the building that houses the church before he suspected the mural was there. Cho and the church’s elders wanted to find a larger space, but they weren’t ready to sell and the Chouinard group secured a building in South Pasadena.

The mural has raised the issue again, with new urgency, and the climate seems to have changed. Tourjé and Cho are talking about relocating the church and hope to devise a mutually agreeable plan that would let the Chouinard group take back the school’s former home and restore the mural.

“Art belongs to the community,” said Cho, who was born in Korea, educated in Philadelphia and moved to Los Angeles 16 years ago. “I love this city, but this area does not have special art and we want to help. I hope the mural will be restored. It would be good for the com- munity.”

The revelation that the mural lives – in some form – was sparked last June by research on another project. Luis Garza, and independent curator who is organizing a Siqueiros exhibition expected to open in September in Los Angeles’ Municipal Art Gallery, phoned leaders of the new Chouinard in South Pasadena. Hoping to find information on “Street Meeting,” he and associate Jose Luis Sedano set up a meeting with artist Robert Perine, who graduated from Chouinard in 1950 and spearheaded the school’s revival with Tourjé. Perine died in November.

“We had started some archeological digs on the mural,” Garza said. “We knew the names of artists who had helped Siqueiros with the Chouinard mural, and we hoped to find visuals and background material.”

At the meeting, Garza, Sedano, Perine and Tourjé looked at photographs of the mural and speculated about where it might have been painted. Perine suggested a wall adjoining the actual site. Then No buyuki Hadeishi strolled in. a former Chouinard student and teacher who serves on the new school’s board of directors, Hadeishi hadn’t previously seen the pictures, when he took a look, he immediately pegged the location of the mural.

“I was very familiar with that area because I taught print- making next door to it,” Hadeishi said, “and I set up a photography dark room in the space behind the windows in the mural. The reason Bob Perine and others who had seen pictures didn’t realize where the mural was is that a roof had been built over the first floor. You can’t see the whole wall.” Floor plans of the building, published in a 1985 book by Perine, proved

that Hadeishi was right. A door on the first floor and three windows on the second floor cor-respond to those in the mural.

Brimming with curiosity, Tourjé headed off to the church early the next morning. Above a door in the church’s kitchen, he found a nail hole that ex- posed several layers of paint, including a bit of bright color.

“Then I went up on the rood to see the top of the wall,” Tourjé recalled. “It was breathtaking to look down and see incised lines that correspond to the design of the mural. You wouldn’t no- tice them if you weren’t looking for them, but once you know, there’s no question.”

After a long talk with Cho, Tourjé relayed the news to the curators and his Chouinard colleagues. Pooling resources, the Chouinard group came up with a few thousand dollars and established the Chouinard/ Siqueiros Mural Conservation Fund. Then Tourjé consulted with paintings conservator Carolyn Tallent, who referred him to Rainer, a mural specialist. She enlisted colleagues Chris Stavroudis and Aneta Zebala, and they scheduled the first of several visits.

In the meantime, Tourjé found a loose section in a patch on the exterior mural wall. He covered the rupture with protective tape, but a chunk of plaster came off, revealing bright red paint and shapes that precisely match the shoulder of a laborer in the mural.

That ragged spot remains the most “tantalizing” indication of buried treasure, Stavroudis said. But the conservators have removed paint in several tiny sections, called “re- veals,” offering hopes of more to come. Bright blue tape covers their tests on the exterior; reveals in the kitchen dot a wall largely obscured by massive refrigerators.

“We are cautiously optimistic,” said Rainer, whose team will prepare a report of their findings and make recommendations. “We do feel that something is there. We can see traces of the design through paint and plaster layers. We can see incisions that march the historic images. And we do see color, but some of it may have been scraped before the wall was repainted. We also see big patches of plaster on that upper exterior wall, and we have heard that large pieces of plaster fell off in an earthquake in the 1990s. But we can’t know how much has sheeted off or what condition the mural is in until the whole thing is uncovered.”

The wall has four zones that would require different treatments, Rainer said. Exterior paint would be removed me- chanically, but scraping. Each of the three interior sections an attic above the drop ceiling, the upper painted wall and the lower tiled segment – probably would call for a specific application of solvents. Devising these systems would be part of the challenge, she said.

But no campaign will be launched for a while – if at all. “When we produce our report, we will advocate for not doing anything more until the build- ing is secured and there is an owner who has a long-term preservation plan for the mural,” Rainer said. “The next step would be to do larger tests in every area and find the best, most efficient way to remove the paint. But we want to do the project in a comprehensive way. We don’t want to do any more testing on the exterior until it is protected by some sort of covering, and we don’t want to work on any one area without knowing about the other areas.” The perpetually troubled conservation of “América Tropical” casts doubt on any attempt to restore “Street Meeting.” Goldman tried to stir up interest in preserving the Olvera Street mural in 1969, but work didn’t begin in earnest until 1987, when the Getty Conservation Institute joined forces with El Pueblo de Los Angeles Historical Monument, the city department that administers the site. Progress has been fitful and the Getty has threatened to withdraw the balance of its$2.6-million commitment if the city fails to raise the estimated $1.4 million needed to complete the work. The Getty’s deadline is July 1. If all goes well, the project will be finished at the end of 2006.

Despite the specter of fundraising, Tourjé said that private ownership may be an advantage for the Chouinard project. Undaunted, he and his colleagues envision acquiring the old building as part of a complex that would include the school in South Pasadena and serve as a beacon of Southern California’s artistic legacy.

“It’s our idea of urban cultural development,” he said. “The mural could potentially become an icon, as an identity factor for the larger surrounding community – both His- panic and Asian, due to Pastor Cho’s contribution to the idea and the larger L.A. art community.”

Chouinard school to host conversations with artists

The fledgling Chouinard Foundation School of Art in South Pasadena will launch a visiting artists series this weekend with appearances by Larry Bell and Ed Bereal. The program will be the first public event at the school, under con- struction in a historic two-sto- ry building at 1020 Mission St.

Bell and Bereal – alumni of the school’s predecessor, Ch- ouinard Art Institute, which closed in central Los Angeles in 1972 and evolved into CalArts in Valencia – will conduct what they describe as a freewheeling conversation about creativity and artistic integrity tonight at 8. They will teach a master class Sunday from 2 to 4:30 p.m.

The weekend program is part of a five-year effort to re- create Chouinard that began when artist and contractor Dave Tourjé bought a fixer- upper in South Pasadena and discovered that it had been the home of the original school’s founder, Nelbert Chouinard.

Tourjé had no connection to the school but became fas- cinated with it and obtained the support of painter Robert Perine, a Chouinard alumnus who chronicled the school’s history in a 1985 book. They es- tablished the Chouinard Foun- dation in 1999, then organized an alumni exhibition, held a benefit art auction and leased the Mission Street building.

Renovation of the 16,000-square-foot structure is about two-thirds complete, Tourjé says. Meanwhile, the school’s first 63 students are taking classes in drawing, de- sign and color theory at the un- finished facility.

Tickets to the artists’ con- versations, “Bell and Bereal in Dialog,” cost $10. Tuition for the master class is $50. In- formation: (323) 982-1773 or info@chouinardfoundation. org.

Defunct L.A. art school on a quest for resurrection

A group of artists is raising money in hopes of reviving Chouinard Art Institute, which closed its doors in 1972.

There’s no point in starting another art school – unless it’s education- ally unique, it’s run by practic- ing artists, it’s based on student needs, it re-focuses on fun- damentals, it has community support, it has solid financial backing and it has a meaning- ful name.”

That’s the message on the cover of Grand View, the Quar- terly bulletin of the Chouinard Foundation, a nonprofit orga- nization in South Pasadena. It’s also the rallying cry of a group of artists who hope to create a new version of a long-gone, much-mourned Los Angeles art school, Chouinard Art Institute.

The school, founded in 1921 by artist and teacher Nelbert Murphy Chouinard, closed its doors on Grand View Street in 1972 and, with the help of Disney money, evolved into CalArts in Valencia. But Ch- ouinard has a lively presence in L.A. art history because dozens of prominent artists worked or studied there. Remembered as a freewheeling environment that taught the basics and fos- tered creativity rather than pro- moting a particular style, the school inspired fierce loyalty.

Supporters of the Choui- nard revival, who have already leased a building in South Pasa- dena’s Mission Street corridor, are gearing up for their first major fund-raiser. It’s an auc- tion of artworks donated by former Chouinard students and teachers, to be held at 7.15 at the I.M. Chiat Gallery in Beverly Hills. Works to be auctioned will go on view Monday in a preview exhibition that will run through March 15.

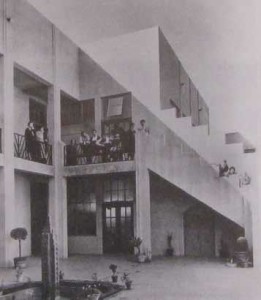

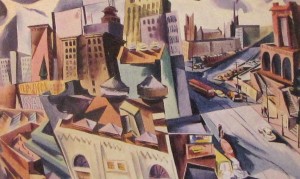

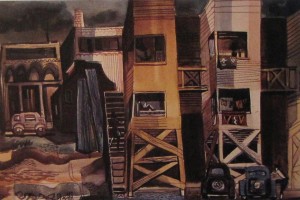

MULTIPURPOSE: The Chouinard Art Institute, shown here in 1949, trained everyone from painters to cartoon animators.

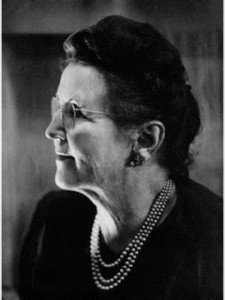

FOUNDING MOTHER:

Nelbert Murphy Chouinard.

The exhibition and sale will celebrate the talents of a wide range of artists who were in- volved with Chouinard, says artist and contractor Dave Tourjé, who established the Chouinard Foundation in 1999 with Robert Perine, an artist and author of “Choui nard: A Vision Betrayed,” a 1985 book that chronicles the school’s history and bemoans the merger with Disney money and CalArts.

They hope the auction will raise $500,000 toward a goal of $2 million to renovate the building and establish the school. So far, the foundation has received more than $100,000 in cash, in addition to donated artworks, Tourjé says.

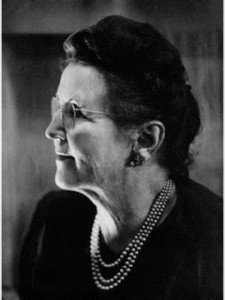

The auction will offer works by about 100 artists, including the late Emerson Woelffer, an abstract painter who taught at Chouinard from 1959 to 1970; Frederick Hammersley, a noted painter of hard-edge abstractions who was on the faculty from 1964 to 1968; and Ed Rus- cha, the quintessential L.A. art- ist who studied at Chouinard from 1958 to 1962. Among other works that will go on the block are a painting by Disney animator Marc Davis, draw- ings by Playboy cartoonist John Dempsey and works by Guy Dill, Larry Bell, Joe Goode, Phil Dike and Millard Sheets. There are also works by artists with no direct Chouinard experience: Gajin Fujita, in his 30s and a product of Otis College of Art and Design and the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, is repre- sented with a work.

The foundation is also sell- ing a commemorative print, featuring the image of Nelbert Chouinard’s circa 1915 painting “Eucalypti.” The hand-printed serigraph, published by Cirrus Editions as a limited edition of 375, is priced at $1,000.

The movement to re-create Chouinard began is 1998, when Tourjé bought a fixer-upper in South Pasadena and discovered it had been the home of Nelbert Chouinard. Although he had no connection to the school, he did some research, read Perine’s book and looked up the author. They started talking about the possibility of reviving the vi- sion of the school’s founder, set up the foundation and began to use the house for reunions, seminars and small exhibitions.

The foundation made its first public splash in 2001 with a three-part exhibition of art- works by Chouinard affiliates at the Oceanside Museum of Art, Palomar College’s Boehm Gallery in San Marco and Mira Costa College’s Kruglak Gal- lery in Oceanside. That event dusted off the school’s history, but the auction is intended to bring it back to life.

Whether Chouinard can be revived remains to be seen. Some of the artists who have donated works to the auction privately question whether Southern California needs an- other art school, in addition to Otis College, Arts Center Col- lege of Design, CalArts and a host of university art departments.

But the new school would be different, its advocates say.The idea is to offer “a con- centrated, professional, fun- damentals-loaded approach taught by experienced artists using actual problems they have confronted,” says painter Walter Gabrielson. “That’s what Chouinard was about. They didn’t teach dogma. Now art schools have reversed that; they teach dogma and hardly any fundamentals.”

CALENDAR

LETTERS

Chouinard and CalArts

ERRORS in Don Mann’s Aug. 5 letter should be cor- rected to reflect actual events occurring during the cre- ation of CalArts and its absorption of the Chouinard Art Institute and the Los Angeles Music Conservatory. Mann attributes a large part of the responsibility for these events to Bob Haldeman, who resigned from the board in 1970 and had nothing to do with events Mann describes, which occurred in 1972. Similarly, he incorrectly refers to Harrison Price as an accountant and owner of the accounting firm Price Waterhouse. Mr. Price is, however, a trustee of CalArts, which he has generously served for 40 years. Edward Reep and Bill Moore were never board members.

The merging of CalArts and Chouinard was indeed painful. Walt Disney was gone, and the board of trust- ees had installed a new administration under the presidency of Robert Corrigan. This new administra- tion absorbed some faculty and some programs from Chouinard and the conservatory, but many programs were modified or abandoned in favor of the new direc- tions. The board delegated the business of defining the new academic structure to the administration, which had been brought in to do that job. At times, several trustees took issue with some of these choices.

Nevertheless, CalArts was positively influenced by merging with its two antecedent schools. The bottom line is that mergers are not easy. In this case, however, the quality of the result honors both Chouinard and the conservatory.

STEVEN D. LAVINE

President, California Institute of the Arts

Valencia

MANN indicates that the “New York academics” Cathleen Cross Ohanesian was referring to in her prior letter were H.R. Haldeman and Harrison Price. She was in fact referring to Robert Corrigan and provost Herbert Blau, who resigned in the wake of the chaos surrounding the Chouinard/CalArts transition.

The existing relationship between Chouinard and Cal- Arts is clearly a complex one.

Since buying Nelbert Chouinard’s home and co-found- ing the Chouinard Foundation with Robert Perine, I see that the passion this discussion inspires has at its roots the loss of an important art-education system, one that amply succeeded before its awkward end.

To completely blame Corrigan and Blau for the demise of Chouinard would be shortsighted. The ultimate re- sponsibility lay in the hands of Nelbert Chouinard and Walt Disney themselves: hers for allowing the financial condition of her school to deteriorate to the point of needing Disney and his for not preparing an orderly transition of Chouinard affairs in the event of his sud- den and untimely death, which unfortunately occurred. The “what if” theories will likely continue, but what we have is “what is”–a rich yet nearly forgotten legacy that if explored could only serve to strengthen the founda- tion upon which rests the ongoing process of art-mak- ing in Los Angeles and beyond.

DAVE TOURJE

Chouinard Foundation

South Pasadena

Los Angeles Times

CALENDAR

LETTERS

RE the July 8 letter from Cathleen Cross Ohanesian, daughter of the celebrated painter and teacher Watson Cross, in re- sponse to the article about Chouinard Art Institute (“True to a Significant School,” by Suzanne Muchnic, July 1): While I did not attend CalArts during the period her father taught there, my good friend Edward Reep was the chairman of the painting department and one of Cross’ mentors. We were both surprised and saddened to read her bitter and grossly inaccurate inter- pretation of Walt Disney’s ideals for CalArts.

Chouinard was indeed to be dissolved into the new campus of CalArts, which was to be made up of five separate schools of art, under the direction of a board, with Mr. Disney, Mr. Reep, Bill Moore, Millard Sheets and Robert Corrigan, a doctorate in dance, among others. They were thrilled to be a part of an exciting new school infused with a great deal of new capital. The only thing we can possibly fault Mr. Disney for is contract- ing cancer in 1966 and subsequently dying from the disease in December of that year.

The “New York academics” Ohanesian refers to were none oth- er than H.R. Haldeman, who left CalArts to go do some kind of work in Washington with the Nixon administration, and his re- placement, Harrison Price, the accountant and owner of Price Waterhouse who caused the mass attrition in 1969. To blame Walt Disney for the demise of Chouinard in 1972 is blatantly unfair.

For anyone really interested, there is a book titled “Chouinard, an Art Vision Betrayed” by Robert Perine.

DON MANN

Van Nuys

Los Angeles Times

CALENDAR

LETTERS

Disney and Chouinard

IWAS gratified to read Suzanne Muchnic’s story about Ch- ouinard Art Institute (“True to a Significant School,” July 1). The impact this school had on the art world in this country cannot be overestimated.

My father, Watson Cross, graduated from Chouinard, and for 29 years was one of the life drawing and anatomy instructors. Many of the painters, sculptors, fashion designers and anima- tors who passed through Chouinard were in his classroom near the start of their careers. He was proud of them all and proud of the “creative training ground” that was Chouinard.

Most of the teachers and students were at first exhilarated at Walt Disney’s interest and patronage of Chouinard. Unfor- tunately, as Disney became the school’s benefactor, he also became its destroyer. His idea of a university of the arts was a good one–the fact that CalArts has survived attests to that. Clearly, Chouinard and most of its faculty did not fit his tidy, Disneyland Main Street, U.S.A. vision of a factory far removed from the gritty city, churning out talent to feed his empire. The New York academics Disney brought in to head CalArts dis- carded a dedicated, proven faculty and killed the spirit that was Chouinard.

We will never know what the future might have held for Ch- ouinard if Disney had infused it with money but allowed it to remain its free-spirited, experimental self. Its demise in 1972 left a void in Los Angeles’art education as yet unfilled.

CATHLEEN CROSS OHANESIAN

South San Gabriel

Los Angeles Times

CALENDAR

TRUE TO A

SIGNIFICANT

SCHOOL

Faculty and alumni have joined a show on freewheeling Chouinard’s place in Los Angeles art history.

Chouinard Art Institute closed its doors 29 years ago, but it refuses to die. Even if the building on Grand View Street, just west of downtown Los Angeles, is now the home of the Korean American New Times Church and the school has long since evolved into CalArts, way out in Valencia, fond memories of the long defunct school pop up in nearly every panel discussion, symposium, lecture and article on L.A.’s art history.

Still, there has never been a Chouinard love fest like the exhibition of works by 137 former members of the school’s faculty and student body scheduled to open Saturday and run through Aug. 26. Presented by the Chouinard Foundation a nonprofit group dedicated to preserving and expanding the legacy of the school’s founder, Nelbert Chouinard and sponsored by the Oceanside Museum of Art, “Chouinard: A Living Legacy” is a three part show. “The Early Years: 1921- 1945” will be at Palomar Col- lege’s Boehm Gallery in San Marcos; “The Middle Years: 1946-1955,” at Mira Costa College’s Kruglak Gallery in Oceanside; “The Last Years: 1956-1972,” at the Oceanside Museum of Art.

Chouinard’s staying power is largely due to the stellar ros- ter of artists affiliated with the school during its 51 years of operation, from 1921 to 1972, and its role in shaping South- ern California Modernism in all its eclectic manifestations.

In 1936, students congregate on the patio.

Rather than being identified with a particular style, the school is remembered as a freewheeling environment that fostered creativity while training everyone from painters and sculptors to animators and fashion designers. It also inspired fierce loyalty, evidenced by the large number of Chouinard students who returned to teach there.

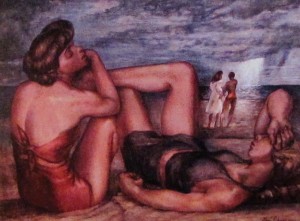

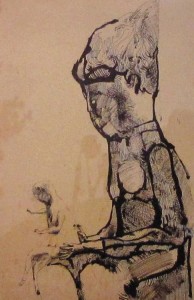

Teacher Marc Davis’ “Woman in Chair.”

Painters John Altoon, Lorser Feitelson, Frederick Hammersley, Matsumi Kanemitsu, Millard Sheets and Emerson Woelffer were among the faculty’s leading lights, as were ar-chitects Richard Neutra and Rudolf Schindler, Disney animator Marc Davis, costume designer Edith Head and critic Jules Langsner. In addition to those who had lengthy gigs at Chouinard, Russian born sculptor Alexander Archipen ko, French painter Jean Char- lot, Mexican muralist David Alfaro Siqueiros and other international art stars passed through as visiting professors.

On display is “silent II” (1971) by Matsumi Kanemitsu, a Chouinard teacher.

For many alumni, Ch- ouinard (pronounced Shuh- NARD) was exactly the right place at the right time. Take artist Edward Ruscha, L.A.’s quintessential artist. He headed west in 1956, fresh out of high school in Oklahoma City and full of plans to become a sign Pasadena). He was crushed to discover that the school of his dreams had no room for him, but it turned out to be a good thing. “Art Center had a dress code no facial hair, no sandals, no affectations of beatnik culture,” Ruscha said, rolling his eyes. After asking around, he landed at the relatively casual Chouinard, which suited him much better.

Robert Perine, a painter and graphic designer who lives in Encinitas, Calif., was sloging through required courses at USC on the GI Bill in the late 1940s when he decided to transfer to Chouinard. “I was in heaven,” he said. “Every day I could draw and paint.” In 1978, 28 years after his graduation, Perine was still so infatuated with the school and so distressed by its transformation into CalArts, with the help of Disney money that he began conducting interviews and compiling information for a book, “Chouinard: An Art Vision Betrayed,” his chatty, opinionated but ambitiously researched account of the school’s history, was published in 1985.

The exhibition is intended to “put Chouinard in its proper context as the vital Los Angeles art institution it was” and to give “full credit to Nelbert Chouinard, a woman who was ahead of her time,” said Perine, who curated “Chouinard: A Living Legacy” with artists James Aitchison and Ed Flynn. It’s the first public project of the 2-year-old Chouinard Founda- tion, and the organizers hope it will inspire other curators to delve into the school’s history.

As for the founder, Nel- bert Murphy Chouinard was born in 1879 in Montevideo, Minn., and studied art at Pratt Institute in New York. She moved to California is 1909 to teach design and crafts at the Throop Polytechnic In- stitute (now Caltech). In 1916, she married Horace “Bert” Chouinard, an old friend from Minnesota who was serving as a U.S. Army chaplain, and they moved to Washington, D.C. He died of cancer a year later and Nelbert returned to California.

She taught art history at Otis Art Institute for a couple of years and opened her own school in 1921. With $250 in cash, a World War I widow’s pension of $75 a month and two other teachers, F. Tolles Chamberlin and Patti Patterson, she established Chouinard School of Art in a two-story house at 2606 W. 8th St. It was a modest operation that embodied the vision of a woman remembered for upholding high standards while treating her students like members of her family and insisting that “talent is more valuable than tuition.”

Firm but nurturing, she was a formidable character with two faults, Perine said. “Focusing on art, she paid too little attention to finances and, where students were concerned, was generous to a fault. While awarding too many scholarships, she was failing to keep an eye on book keepers,” he said, noting that two of them embezzled funds and put the school in debt on two occasions.

Money was always a prob- lem at Chouinard, but Walt Disney discovered the school in 1929 and began sending his employees there to perfect their drawing skills. The following year, the school was flush enough to move into a new building on Grand View Street designed by the architectural firm Morgan, Walls and Clements. In 1935, the school was reincorporated as Chouinard Art Institute.

The building was financed by an investment company and leased to the school. It was an affordable arrangement at the time, but World War II decimated enrollment and the school was forced to move into a less expensive facility nearby. After the war, the GI Bill reversed Chouinard’s fortunes. Overflowing with veterans who were financed by government funds for education, the school moved back to Grand View and bought the building in 1949.

Artist Ned Jocoby remem- bered Chouinard in the 1940s as “a place that had an almost magical sense of common spirit. There was virtually no disci- pline but everything you needed to learn was there to have if you wanted it. And we wanted it. Often we learned as much from the others in the class as from our teachers who often seemed to be just trying to channel the energy, then standing back to let it happen.”

Painter Walter Gabrielson, who studied at Chouinard in the 1950s, likened the school to “a boiling caldron…where every day teachers and fellow stu- dents were radically reassem bling your head.” Along with one teacher’s “Critiques from hell” and another’s “convoluted problems,” Gabrielson recounted the day when instructor Robert Chuey steamed into the painting classroom, “threw down a load of branches, twigs, beer cans and other junk and yelled, ‘OK, suckers, see if you can paint that.’”

Chouinard was plagued by financial problems in the 1950s. Disney, who became more involved with the school after receiving an honorary degree from it in 1956, dispatched his accountants to sort out the mess and wrote a check to cover the deficit. His interest in the school grew as Nelbert Chouinard aged and relinquished control. He would ultimately choose a board of directors and architects for a new, multidisciplinary university of the arts that incorporated Chouinard and the Los Angeles Conservatory of Music.

Inevitably, tensions devel- oped as Disney’s vision made it clear that the old faculty would be left behind in a school that would cease to exist. Choui- nard devotees hoped that the new institution would at least bear the name of its predeces- sor, but it became California Institute of the Arts, or CalArts, while Chouinard drifted into history.

Nelbert Chouinard, who retired in the early 1960s but maintained a presence at the school for several years, died in 1969. CalArts opened at its Va- lencia site late in 1971. The last graduation at the Chouinard building took place on April 16, 1972.

”Balboa Scene” (circa 1947) by Phil Dike, who taught at the Institute from 1931 to 1951.

Chouinard and its found- ers might have received their final tribute in Perine’s book were it not for a real estate deal in South Pasadena. Dave Tourjé, an artist and contractor, was looking for a home for his family when he came across a rundown, two story house on Garfield Avenue. He kept going back to look at it and finally bought it in the summer of 1998.

While looking over the deed of his fixer upper, Tourjé discovered that he had purchased the home of Nelbert Chouinard. He knew little about the school she had founded and nothing at all about the woman who had lived in the house for many years, but he decided to restore it as close to its original state as possible. While doing research, he found Perine’s book and tracked down the author.

As the two artists tell the story, they hit it off and got excited about reviving Chouinard’s vision. They established the Chouinard Foundation and began to develop plans for granting scholarships to art students and using the house for meetings, reunions, seminars and small exhibitions.

Before long, a group ofalumni was gathering there on Saturday mornings to reminisce and make plans. A newsletter, Grand View, which solicits and prints alumni recollections, drawings and news was launched.

”Lan” by former student GuyDill.

The upcoming exhibition began with talk about presenting works by Chouinard faculty and alumni at the house,but it soon became too big for the space. As more and more artists agreed to lend pieces including Chouinardera and recent works Perine secured gallery space at the Oceanside Museum, where he serves on an administrative committee.That wasn’t big enough either, so he and his colleagues divided the show into three parts and found additional space at the two nearby colleges. Perine cu- rated “The Early Years,” Aitchison organized “The Middle Years” and Flynn rounded up artwork for “The Last Years.”

Now that the show is coming together, the curators are dealing with the usual catalog glitches and delivery problems, but the effort has paid off, Perine said. Just as no one turned down his requests for information when he was compiling his book, the artists have come through with work for the show, he said.

“Chouinard was a school that allowed everything,” Perine said. “It was very free and open. You were encouraged to find where you wanted to go.” The exhibition will reflect that approach in a wide variety of works selected to represent the artists well and when possible compare pieces created during their Chouinard days with later works.

Visitors will see the “diversity of style” that grew out of Chouinard, but they also will see “continuity of quality,” Perine said. Still, the main point of the exhibition and its accompanying catalog is to remind the public of the school’s importance as a creative training ground, he said. “We hope people will see that Chouinard made a contribution to the art of Southern California and beyond.”

“Chouinard: A Living Lega- cy” Saturday through Aug. 26. Boehm Gallery, Palomar College, 1140 W. Mission Blvd., San Marcos, (760) 744-1150, Ext. 2304. Kruglak Gallery, Mira Costa College, 1 Barnard Drive, Oceanside, (760) 795-6657. Both galleries are open Tues- days-Wednesdays, 10 a.m.-4 p.m.; Thursdays, 10 a.m.-7 p.m. Admission is free. Oceanside Museum of Art, 704 Pier View Way, Oceanside, (760) 721- 2787. Tuesdays Saturdays, 10 a.m.-4 p.m.; Sundays, 1-4 p.m. Admission is $5; seniors and students, $3.

LAObserved

Los Angeles media and sense of place

Second Siqueiros mural found

Suddenly Los Angeles is awash in lost murals by Mexi- can revolutionary artist David Alfaro Siqueiros. In 1932, the comrade of Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo came to L.A. to teach a class at the Chouinard Art Institute, the famed private art school that folded into CalArts in the 1970s. While here, Siqueiros painted controversial politi- cal murals on a wall at the school near MacArthur Park and another at Olvera Street. Both were covered over in the antiCommunist fervor of the 1930s. The Olvera Street work, La América Tropical, has been uncovered and is undergoing restoration by the Getty Conservation Institute. The mural painted at Chouinard, “Street Meeting,” had been believed lost.

A story by Suzanne Muchnic in Sunday’s Times (subscribers only) details how some history detectives think they have found the mural, obscured but still intact, on a wall at the old Chouinard campus at 743 S. Grand View Avenue. The former campus, a city historic cultural monument designed by under appreciated L.A. architect Stiles O. Clements, is now a Korean church. The church is cooperating with plans to raise money to further investigate and possibly restore the work. The image above is a later self portrait by Siqueiros.

Chouinard’s influence in the arts in Los Angeles was substantial. It along with the Otis Art Institute formed a thriving arts district around Westlake Park (now MacArthur Park) from the 1930s into the ‘60s. The Chouinard name disappeared in 1972, but artist David Tourjé became intrigued after he bought a South Pasadena home that had belonged to the founder. In 1998, he and a partner started the Chouinard Foundation with an advisory board of former students and faculty. There’s now an art school going and it’s Tourjé who is spearheading investigation of the Siqueiros mural. (Robert Perine, the other partner, died recently.)

When Pratt Art School graduate Nelbert Chouinard moved to California in 1919, a great future awaited her. She began teaching art almost immediately and by 1921, had opened her own school. In less than a decade the Chouinard Art School was listed among the top five art schools in the nation, a position it occupied for the rest of its history. Her faculty consisted of professional artists; students were hand-selected talents, many from local high schools. Her formula was simple: students worked hard at the basics of drawing, design, and painting, and then were encouraged to follow their own learnings. By WWII the school’s reputation had spread and applicants arrived from aroundtheworld. This success continued through the 50’s and 60’s, Chouinard always playing a large role in the development of various forms of Modernism, from Hard Edge to West Coast Pop, Light and Space to Surf and Rock culture. By 1972, Chouinard’s fifty year run had come to a close.

The ensuing thirty years formed something of a distillation period, this process leaving “Chouinard” a purified ideal one that is alive in the many that experienced it and something that reaches beyond even Nelbert Chouinard herself. Part methodology, part lore and memory,“Chouinard,” as it has now become through rediscovery, is clarified and alive, its basic purpose revitalized.

The Chouinard Foundation is a receptacle for this purpose, defining Chouinard’s influential role in the past but, more importantly, being there for future artists wanting to contribute in a meaningful way to the future of art making.

We would like to express our sincere thanks to the artists, dealers and collectors who have generously donated in order to see this idea become a reality.

Robert Perine

Dave Tourjé

Los Angeles, March 2003

DRAWING AND THE ART SCHOOL

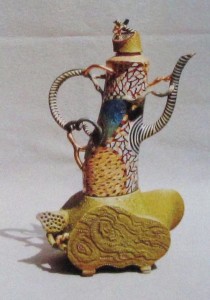

The Chouinard Art Institute was composed of a cluster of related and overlapping disciplines that included fine arts, design, film, illustration, advertising, fashion, and ceramics. It was the conviction of the faculty that a strong general education was required for every student. That education would include history, government, literature, science, psychology, semantics, and two years of art history.